The Hignett family have been handcrafting the finest rocking horses for more than a century. Thought to have graced the playrooms of grand liners like the Titanic, the family’s toys — old and new — are iconic pieces of history. Liverpool carpenter Richard Hignett first turned his hand to toys in either 1899 or 1900; quickly building a reputation for quality. According to family legend, his proudest moment came when he was asked to make a play carriage for Queen Victoria’s grandchildren.

With the help of his children — his son Alfred, who kept the books and his daughter Josie, who made the saddles — he built beautiful rocking horses from a tiny workshop at the family’s humble home in Duro Street. The firm quickly became a respected name and Hignett’s horses began to appear in the most luxurious settings. Notable clients included shipping firms White Star Line and Cunard Lines known for grand cruise ships, including the Mauritania, the Lusitania and the Titanic. To this day, a Hignett horse lies deep in the Atlantic Ocean along with the wreckage of that ill-fated luxury liner.

It is thought that Richard made one of the most famous rocking horses in Liverpool: the original “Blackie,” who excited children visiting the lavish Blackler’s department store. The horse was sadly lost when the shop was bombed in World War II. Despite the firm’s grand customers, Richard didn’t forget his humble roots, building dummy horse bodies for factories to test out saddles for size.

He passed his carpentry skills on to his sons, James and John, who continued to craft the finest horses into the 1930s. The brothers learned that making a good-quality rocking horse is a laborious process. Expensive timber must be carefully selected and crafted with the utmost care to ensure that every Hignett horse can be passed from generation to generation. In 1939, Britain went to war and both James and John were sent overseas, putting the business on hold. When they returned, World War II had taken a deep toll on the country and demand for goods such as rocking horses declined. The brothers could no longer keep the firm in business, and eventually John left to join larger rival Collinson.

John is thought to have had a hand in building a replacement “Blackie” while working for Collinsons. After decades at Blackler’s, the horse was eventually moved to the Alder Hey Children’s Hospital. You can still visit Blackie, who has since been conserved, at the Museum of Liverpool.

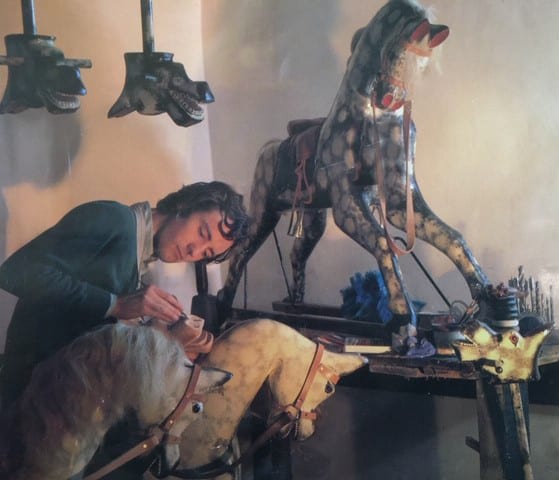

James went on to become a window decorator, but he didn’t forget his carpentry skills. He passed them down to his own son, Jim, who built his first rocking horse aged 11. After graduating from Keele University in the 1980s, Jim began selling his own rocking horses, built with the same techniques used by his grandfather Richard almost a century earlier. Jim turned a room in the Gladstone Pottery Museum into his own “rocking-horse factory,” spending up to a month perfecting each horse. Over the years he has made many horses, with one of his favourites displayed at a U.S. Air Force base in Ipswich.

After working in teaching and in the pharmaceuticals industry, Jim has now returned to the traditional Hignett trade. The only surviving carpenter in the family, he is one of the last remaining links to the thriving Victorian rocking horse industry. Each horse Jim builds and hand paints has its own distinctive character. But you can spot a Hignett’s horse from its famous “Hignett’s twist” — a slight tilt to the neck that gives each horse a dynamic and lifelike quality.